What Quitting Video Games Taught Me About Advertising

About selling technology, earning purpose & killing Nazis

Video game marketing usually falls between two extremes: Bland, meaningless tech babble or cringeworthy attempts at being provocative.

Game developers are experts at UX — yet manage to overlook basic human behavior when designing marketing solutions.

That’s why gaming relies on communities of fans and influencers to share the good news.

Because developers are terrible at communicating outside the tech tribe.

Last week I wrote about storytelling in games from the perspective of a fan — since NDAs prevent me from sharing juicy insider gossip from my time in the industry.

This week I write as a humble observer of video game marketing — the good, the bad and the ugly.

Or rather:

Bad store copy, waste of media and earned purpose through killing Nazis.

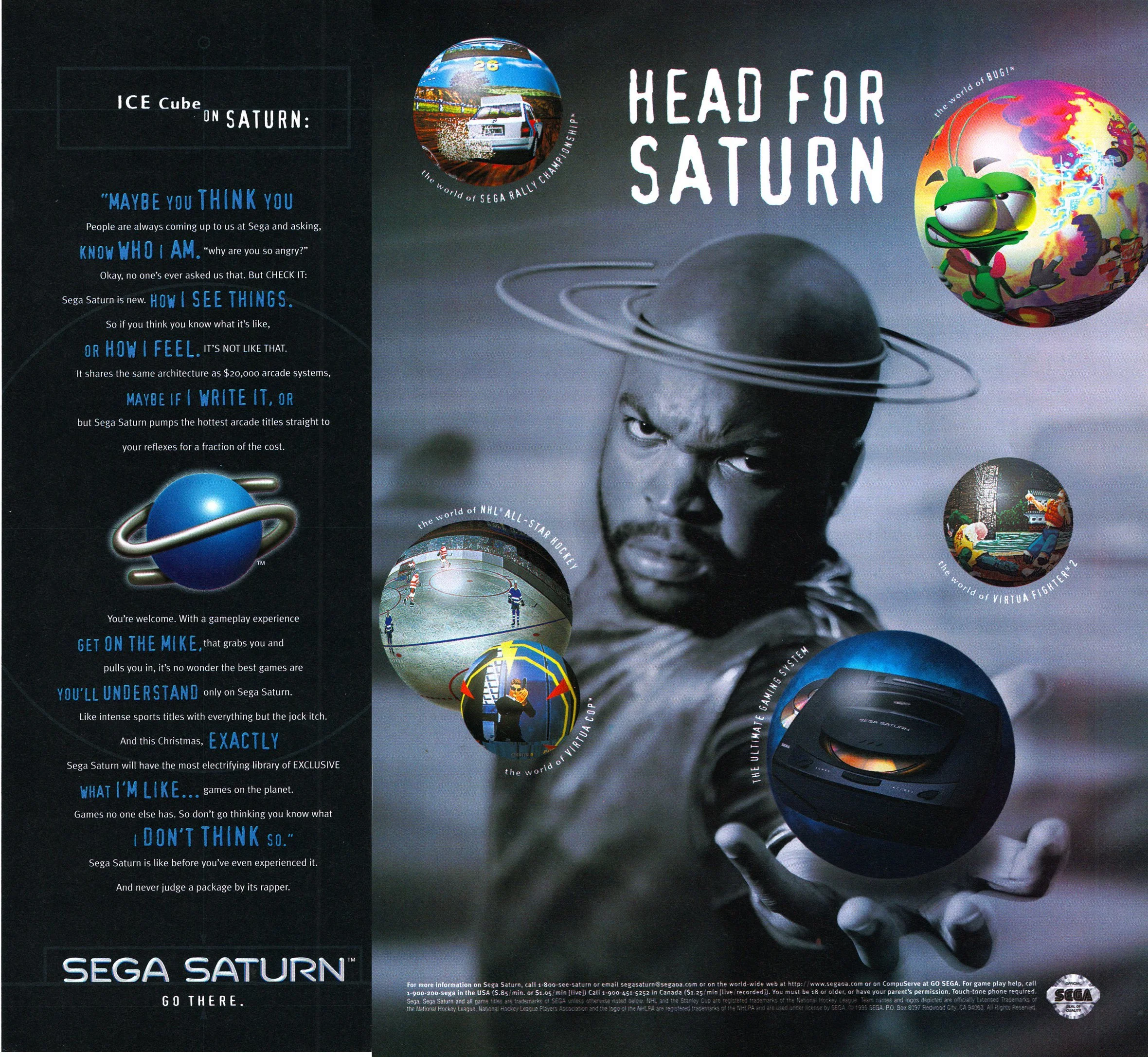

Sell Concepts, Not Products

Legendary copywriter Joseph Sugarman has an important lesson for anyone selling technology:

“You sell the sizzle, not the steak. The only exception to this rule is when the product is so unique or new that the product itself becomes the concept. Take the digital watch for example. When the watches first came out, I could hardly keep them in stock. When I first announced them, my main thrust was to explain the various features, which were all new, and then just take orders.

But as the digital watches became plentiful and everybody understood what they did and how they worked, each ad had to differentiate the features of the watch through a unique concept. For example, the world’s thinnest watch or one with a built-in alarm or one with the most expensive band. Concepts started selling watches; the product was no longer the concept.”

Video game marketing has never outgrown the digital watch.

Gaming made technological leaps in the 80s and 90s — and could simply advertise colorful box art and impressive specs.

For some reason, developers still sell video games as if every single one was a technological wonder.

I got my first taste of copywriting when I worked as a translator and rewrote 2,000,000 words of game store copy, direct mail and random app text from English to Danish.

It was mostly empty superlatives and endless lists of specs.

And always looked something like this:

Venture into an epic, immersive world with deadly weapons and dangerous monsters.

Includes new side-missions, P2P and P2E multiplayer, access to additional content and the new Team Death Mode.

Ultra 4K supported, performance optimized for SSD, ultra-low latency and Real Time Traction.

Enjoy this exclusive experience with 4 million other players — BUY NOW!

That is gaming’s version of an AIDA model (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action).

The first line of generic description is supposed to capture your attention. Then you get a bunch of features to entice you and a third line of technological possibility that is supposedly desirable — if only to engineers. Finally, there’s an uninspired CTA and abracadabra, you’ve read four lines of nothing.

I don’t know what’s worst. The bland descriptions, the redundant adjectives, or the concerning assumption that tech specs will spark hidden desires… Maybe the real sin is the questionable attempt at using both scarcity and social proof in an inefficient mishmash? Or just the failure to translate features into any kind of benefits; copywriting 101?

Of course, the description above isn’t real. It’s my own little parody and surely it can’t be that bad.

Well, if you don’t believe me, I encourage you to check out Steam Store or PSN Store and see for yourself.

Copywriting in the world’s biggest entertainment industry is a sorry mess.

Recommended reading for any marketer.

AIDA gets a bad rap but it’s not just a model for store copy and sales letters. It’s basic storytelling. You catch someone’s attention, make the story interesting, evoke emotion and leave your listener with something that makes them think or act differently.

I don’t know what the gaming story of tech specs is about. Maybe that of engineers marketing to ideal consumers?

In the very first essay for this blog, I called it The Sin of Punk.

But really, it’s the Sin of Tribal Speak.

It’s the error in the echo chamber where engineers forget they are selling creative concepts to human consumers and not technological products to programmers.

Whenever I buy a video game online, I am saddened by how poorly the end of my consumer journey is designed. For the casual fan scrolling through the store, the wall of generic copy makes it hard to tell one game from the other. And even when I know what I’m buying, the uninspired tech babble does nothing to upsell the Deluxe Edition.

If your copywriting is only relevant to hardcore fans who’ll buy the product anyway, you are preaching to the choir — and marketing to no one.

Tribal Calls In The Right and Wrong Places

In spite of crappy copywriting and underwhelming store UX, 94% of all video games are sold via digital channels. The real marketing happens through communities, influencers, and word of mouth. The casual consumer browsing in the store gets nothing because the marketing is for the fans and forgets the rest.

Historically, gamers have marketed to each other at conventions and in forums — even before Reddit gave us subreddits for literally everything.

In deeply engaged communities of believers, a small gesture — like Rockstar’s tweet to announce Red Dead Redemption 2 — can make tidal waves and activate hordes of brand ambassadors.

It can be as simple as showing 1 minute of gameplay followed by a release date:

Not for all audiences.

60 seconds of action and an activating tagline, “Come Slay With Us” + a date of availability.

At a convention with excited fans of the classic game Left 4 Dead, the video above would have been awesome.

A room full of gamers equally full of expectation need nothing more.

Left 4 Dead from 2008 revolutionized team shooters and even if the zombie trend is long over, the spiritual successor is bound to catch the attention of brand believers.

At Comic-Con, I’m sure this spot would in fact slay.

Unfortunately, I was once more reminded that gaming doesn’t understand advertising when I saw the 30-sec version of the trailer on flow TV while watching Sunday Night Football on NBC.

You know… Old-timey television, NFL players getting concussions, interrupted by commercials.

Here the edited trailer appeared as a short and bloody blip between beer and shaving spots.

What’s the concept?

Flow TV isn’t Comic-Con. Showing 30 seconds of gameplay to unassuming football fans without any context seems insane to me.

If you like horror movies and somehow never played a video game, I’m sure it can draw you in. But if you’ve played just a few, it can look an awful lot like a million other zombie titles. And if pop culture has left you numb to the lure of the living dead? You’re long gone to the kitchen or your phone.

Only if you’re a gamer watching football on NBC, know the brand history of Left 4 Dead, and aren’t put off by the generic style… This commercial is for you!

Maybe I’m out of touch with the average NFL fan. But it sure seems like a call to a very specific kind of nerd and not for flow TV at all.

If the quality of copywriting in gaming tells the story of an industry blinded by tech specs, the B4B spot tells the story of someone who bought the big media deal but forgot to make a commercial.

Football Sunday — where gamers get together?

The Back 4 Blood TVC is not an example of bad advertising in video games.

It’s an example of most advertising in video games.

Of using nerd signals in the wrong context and tribal calls through mainstream channels.

Brands and marketers sometimes assume shared interest to a fault, enter tunnel vision on ideal consumers and forget the real-life situations where the advertising is perceived. Gaming and tech more so than most.

Maybe it’s the hubris of masterful UX that makes the gaming industry forget the fundamentals and deliver meaningless copy at store level and waste money on gameplay trailers during football games.

But I don’t like to be a downer.

It’s only been three months since I left the gaming industry and this isn’t a bitter break-up song.

Sometimes video games get it wonderfully right!

One campaign especially fills me with joy and brings up a good point.

It was when Wolfenstein made right-wingers go crazy because… the game had Nazis as bad guys?

How Killing Nazis Became Advertising

When Bethesda released the game “Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus” in 2017, it created a small shitstorm among Neo-Nazis and right-wing extremists — and a love storm from everybody else. Simply because the game was about defeating Nazis and the advertising stood by it.

The first Wolfenstein was released in 1981 and the series currently counts 13 games, all centered around WWII and the fight against Nazis.

2017’s contribution was set in an alternate universe where Germany had won the war. The action focused on the 1960s where the US was occupied by The Third Reich and right-wing movements like the Ku Klux Klan had increased their power through collaboration with the invading forces.

Which offended real-life members of the KKK!

Snowflakes.

Even though the story and concept had been written years earlier, life was imitating art when white supremacists marched through Charlottesville in August of 2017.

Bethesda seized the moment and came up with the tagline “Make America Nazi-Free Again”, mirroring Trump’s slogan while still being very much rooted in the game and brand DNA.

It’s a fine line between showing purpose and flashing empty virtue signaling — but when the core product has been about defeating Nazis for 36 years, you’ve earned the right to advertise it.

By playing into the ongoing political climate with a narrative core that had been in production for years, the ad was demonstrably not born from opportunism but from artistic expression and brand DNA. Paraphrasing the MAGA slogan was simply a way to compare the dystopia of the game to real-life events.

The tweet was simple, tongue in cheek, and asked nothing of you. You had to decide for yourself where you stood.

Getting challenged made the trolls uncomfortable and white supremacists had hissy fits in YouTube comments — but the campaign made international news and got attention far beyond the gaming industry.

When brands get called out for virtue signaling, it’s usually because they are trying to score moral points in an unearned arena.

The critical consumer can easily spot when a brand intrudes on an unearned domain and tries to gain undeserved attention. Like when Pepsi suggested that fizzy drinks and the world’s most overprivileged influencer could stop police violence.

A 36-year-old franchise about killing Nazis has both earned and deserved the right to say “Nazis are the enemy”.

The advertising found its purpose in the brand DNA and the developers had the courage to stand by it. That’s how Pete Hines, VP for PR & Marketing, went viral when Vice asked him if the campaign was poking the hornet’s nest:

“Maybe a little bit. But the hornet’s nest is full of Nazis, so… F*ck those guys.”

The game took a stance — with a core concept and in a domain that had been earned for decades. It displayed brand courage and risk willingness without actually risking too much.

To Americans, it looked like a costly challenge. But Trump had only little support in European and Asian markets which probably made it easier for the Swedish developers to make the bet.

As Hines explained to Gamesindustry.biz:

“As we've said many times before, fighting Nazis has been the core of Wolfenstein games for decades, and it isn't really debatable that Nazis are, as Henry Jones Sr. said, 'the slime of humanity.' Certainly, there's a risk of alienating some customers, but to be honest, people who are against freeing the world from the hate and murder of a Nazi regime probably aren't interested in playing Wolfenstein.”

Sell Truth, Not Virtue

Video games advertise technology when they should be selling concepts — born from the games themselves and not the machinery underneath.

Online store copy reads like engineering manuals and gameplay trailers are assumed to be as enticing to football fans as to a convention full of cosplayers.

And when gaming tries to be “culturally relevant”, it usually fails — like when Call of Duty expressed support to Black Lives Matter and was ripped apart by fans because the series had allowed racist screen names for years.

Wolfenstein got it right by working from the inside out, from the brand DNA and core narrative, and made waves through mainstream media with truth and cultural tension. The developers stood by the message and went viral.

Purpose is fickle and has to be airtight. Anything unearned will be exposed as virtue signaling.

When Joseph Sugarman wrote copy for a chess computer in the late 1970s, he recruited Russian grandmaster Anatoli Karpov as an influencer and used the endorsement for the concept of “The Soviet Challenge”.

Wolfenstein did him one better because it already had its challenge — and could express it in a single tweet: Make America Nazi-Free Again.

Purpose is earned in the product domain: How the product can benefit the world.

Wolfenstein gave players an opportunity to stand up to Nazis. Symbolically and virtually.

That’s a concept you can build upon.

Too much of gaming is marketed on technology and overlooks the potential of the art form itself. We sell tech to tech-heads and forget to communicate outside the tribe.

Technology can be a beautiful trick — but advertising magic is found at the narrative core. Build from there and your purpose is self-evident, your marketing gets meaningful, and your storytelling becomes storydoing.

The gaming industry is wise to realize it’s selling creative concepts, not technical measurements — and remember the words of G.K. Chesterton:

“We perish not for the lack of wonders — but only for the lack of wonder.”