What Failing At Music Taught Me About Advertising

About bands, brands, creation & imitation.

Chapter 1: Fantasy + Trend

“The big idea comes from truth and cultural tension.”

David Ogilvy + a whole bunch of copycats

Word for word those might be the most valuable syllables ever written about advertising.

Because none of them are about advertising.

They’re about any human endeavor that tries to create more than it takes.

Any gesture towards alchemy of the mind.

Really, it’s true for any creation trying to survive on an evolutionary battlefield or in a commercial space.

It goes for advertising, art, comedy, video games, and — in my limited perspective — most of all music.

The truth, however, is a fickle bastard.

It might be what the most people recognize as true — or what the fewest people can shoot down as totally moronic manipulation and deceitful tribal signals.

The truth is the rare thing that no one on the internet can tear asunder in a few hours.

Something old about the human condition that makes life seem new.

Cultural tension is the element of magic that makes the truth worth fighting for.

It’s the note that resonates the most in human hearts and systems of power.

Not only will you know its value — you’ll go share it with your friends.

The Big But

Truth and cultural tension are at the heart of all human communication.

Unfortunately, it’s easy to turn Ogilvy’s beautiful maxim into “Fantasy + Trend”.

Like, damn easy… And it can be profitable. Just never quite as valuable.

It can help you make an effective campaign or produce a successful album.

But it won’t build bands or brands for lasting success.

I think the classic boyband might be the most honest representation of Fantasy + Trend.

New Kids on the Block, One Direction, and the Korean kids I heard last week.

All fairly honest about their use of bullsh*t.

It’s a multimedia make-belief with heavily photoshopped and auto-tuned performers playing a role and imitating the expected values and desires of an audience who doesn’t know any better.

It can turn impressionable minds into Beliebers.

For a while at least.

In the 1960s psychologist Dorothy Tennov dubbed the phenomenon “limerence” when conceptual pop bands emerged and turned churchgoing teenagers into screaming maniacs — possibly possessed by one kind of devil or another.

Four Kids with Fabulous Hair

The original boyband to use Fantasy + Trend on an easily swayed audience consisted of four longhaired heartthrobs back in the 1960s.

Of course, I’m talking about The Monkees.

Did you think I meant The Beatles?

Because The Beatles captured truth & cultural tension like lightning in a bottle and changed the world with it.

They did it like no one ever had.

The Monkees merely imitated the Beatles’ model and used Fantasy + Trend to sell a mediocre product to impressionable teenagers.

The four American copycats did pretty well for themselves. Made some money, had some fun, did all the drugs.

But they never turned the band into a brand because they had nothing of substance to sell. They adopted last year’s model — but had nothing of their own to generate new value. Neither truth nor tension.

The Beatles evolved organically and did their research in the clubs of Hamburg to create something that was both perfect pop and totally unheard of — and just happened to have cultural tension to reverberate so hard in human hearts and systems of power that it birthed a pop-cultural revolution.

Do you want to live like Monkees or build towards the future?

Murder in the Desert

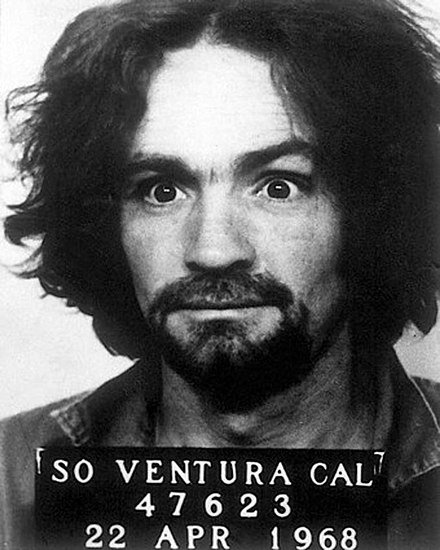

There’s a kind of advertisement that reminds me of not only The Monkees but of someone else who listened to the Beatles — and took pop-cultural symbols and mixed them with reductionist reasoning.

He even managed to turn his own personal brand into a cult.

Charles Manson had the kind of neurological composition that made him low on empathy and bad at understanding consequences.

With little empathy but above average IQ, Manson lacked the emotions to grasp long-term relationships but had the pattern recognition to identify successful short-term interactions.

He learned to hack the humans around him for quick solutions to “Charlie problems”. And as a drifter in and out of prison, he rarely stuck around long enough for his bullsh*t to catch up.

In the Californian desert, Manson found the perfect storm in an impressionable audience of abused teens, isolation from critical thinking and a whole lot of drugs to turn a fragile ego’s power fantasy into bloody murder.

Does it surprise you that he considered himself a musician?

He reminds me of a kind of advertising that — with all the elegance of a sadist — can activate a very specific target audience using flash, cheap manipulation, and power words of the week.

It can be measurably effective.

Consumers have their buttons pushed and are activated.

It can look like a good solution to both clients and agencies.

Sometimes there’s enough systemic bias to blind even the best creatives and wisest strategists.

I suppose that’s why we need more outsiders in advertising.

Because to everyone else, the measurably effective button-pushing looks like a sociopath trying to lure someone into a white van with vague promises of community or romance.

To anyone outside the targeted segment, it looks like a warning sign written across the sky:

“Creep Express — Straight to the Desert”.

Do people really need more reasons to hate advertising?

With glass house brands and the full fury of the internet, why do we still assume that old-world conmanship will do anyone any good?

Never let the dude with Manson vibes write the mission statement.

Those guys have a tendency to seriously mess up manifestos!

Tear Down to Build Better

Manson took the most punk rock song of The Beatles — Helter Skelter — and mistook the radical new for destruction of the old.

Punk and rebellion are essential to any creative endeavor.

Ogilvy agreed:

“Talent, I believe, is most likely to be found among nonconformists, dissenters, and rebels.”

However, the point is not to destroy — but to deconstruct.

To always remind us that any and all of our systems are temporary and reductive interpretations of much more complex human challenges.

Even the most abrasive noisecore exists to create.

Not to abuse or imitate for short-term success.

But to make the world bigger by changing the way you think about it.

Are safety pins dangerous symbols made safe?

Or safe symbols made dangerous?

When I look at the example of The Beatles, The Monkees and The Manson Family, I don’t see three creative models.

I see three business models — and only one of them created lasting value.

Why do less?

Be Beatles.

Chapter 2: Music & Me

Big talk about being The Beatles from someone who failed at music.

And it’s true.

I did fail at music.

I spent a surprising amount of my life as a songwriter, music producer, sound engineer, audio designer, and DJ — considering I have no real talent for music.

Not in the traditional sense anyway.

I was a Dungeons & Dragons nerd who liked poetry.

Who quickly discovered that unpublished poet is the most friendless, sexless type of artist you can be.

If you can play a few chords, write a rhyme and sing your heart out, you get much cooler friends and considerably hotter lovers.

I know at least a few creatives in advertising who did their first re-branding simply by figuring out how their eccentricities could be framed in a slightly sexier light.

It’s how I spent more than a decade doing something I mostly sucked at.

What was I thinking?

Because I love everything about music — except the music.

Wait… That’s not right.

Everything except the math beneath the music.

I mean, it’s important.

In a way it is the core of music.

It’s just soooo boring!

I love everything around the music.

Copywriting legend Eugene Schwartz said it best: “Copy is not written. Copy is assembled.”

That’s what I loved about being a music producer.

How you get to use the musical elements like building blocks to create the most beautiful version of the story underneath.

It’s the deceptive simplicity of words, rhythm, and tone as equal elements but with ever-varying values; changing dynamically depending on their creative and commercial systems.

There’s a lot to love about music other than the notes themselves.

The Producers (not the Mel Brooks movie)

Sucking at the actual job, I had to make up for my shortcomings with creativity and whatever talents I had as a storyteller.

And in a world where everyone is good at kinda the same thing, being an outsider can be quite helpful.

Don’t be that guy.

As a music producer you have to be a creative midwife, stylistic counselor, and sometimes straight-up executioner. Though not in the Phil Spector sense!

You’re the idealistic but pragmatic creative director — always looking for genius but usually ending up making silver look like gold by changing the light a bit.

A good music producer will help the band turn up everything that’s awesome.

A great producer turns down anything that’s not.

These days the rock producer of old is gone.

He died with the small and mid-sized studios in the 00s as the recording business moved into bedrooms and more flexible systems.

Now the brunt of the work is on the mix-engineer turned post-producer.

In advertising terms, it’s like being a freelance copywriter for in-house marketing.

Most of the time it comes down to helping someone who’s made poor choices and wants to do too much with too little.

It’s about swearing out loud (fortunately in a soundproof room) — and then making magic happen anyway.

Good creative work is always detective work — you look for the spark that sets the biggest fire.

You help someone do something that millions have already done.

And you go hunting for that one thing that’s entirely unique and makes the final creative vision slip right into focus.

You learn to shine the light that points out the good and explains away the bad — while also making sure that an audience loves it, a lot of people like it, and a few parents are left confused and/or possibly angry.

In that regard advertising is really is like rock n’ roll.

Only you have to realize that you are George Martin and not John Lennon.

John Lennon with legendary producer George Martin — not related to Chris Martin.

Chapter 3: MAYA & the Pop-Punk Spectrum

Why industrial design and behavioral science are music to my ears

If you like to nerd out about creativity and its philosophical implications, this is where it gets good.

But if you — like me — have a hard time keeping focus, there are some videos to enjoy as the mind wanders.

We might not know each other well enough for you to trust me through this long an essay.

But are you still with me? Then you’re a champion and I hope we can hang out!

Are You a Friend of MAYA?

Industrial designer Raymond Loewy came up with the MAYA principle for his creations.

“Most Advanced Yet Acceptable”.

It describes the sweet spot between the neophile and the neophobe of the human mind.

The constant struggle between lust and fear of the new.

Even if you don’t know Raymond Loewy, you know his work.

It’s also the perfect description of a great pop song.

The ideal arrangement of sound that is totally recognisable as a massive stadium banger — yet something no one has ever heard before.

And much like truth & cultural tension, it works equally well for almost any kind of communicated creation.

Optimisers & Satisficers — Pop vs Punk

Cognitive psychologist and economist Herbert A. Simon was one of the first to introduce the distinction between maximisers and satisficers; the former being ideal consumers who look for maximum value and the latter being a neologism of “satisfy” and “suffice” — describing real people who make good-enough-decisions under unideal circumstances.

Creatives and creators tend to think like maximisers and assume their audiences do the same.

Sometimes I call it “the sin of punk”.

By punk I don’t mean the actual genre.

Most punk rock tunes are just pop songs with more distortion.

I’m talking about the challenger, the avantgarde, the movement towards always deconstructing the systems — musical or otherwise.

It’s the rebel’s desire to challenge the old and the neophile’s desire to build something new.

Japanese noise artist Merzbow made an album using only rocks, stones and pebbles.

That’s the punk ethos:

F**k your expectations, this is music!

Great for art — but a little too advanced for commerce.

Punk is a Brand Language — but Brand Language isn’t Punk

I think of pop and punk as a spectrum of satisficing invitation and optimised exclusion.

Pop is for people who value the social proof of popularity over the scarcity of originality.

Punk is for optimisers who’ll travel longer and harder to get away from the mainstream.

Social proof: At least someone calls it music.

Here’s a fun exercise:

Punk comes down to the activation of inherently tribalistic exclusivity signals to negate the risk of the inauthenticity, uncaring satisficers, and inflexible systemic expectations of mainstream society.

Let’s see how your brain responds to that statement.

If you understand every word, you’re all good.

Or rather, we’re all good.

Because you also get a boatload of signals that we’ve read some of the same books and both earned our place in a “smart tribe” — even if the signals are rather superficial and the statement itself fairly convoluted.

But if the academic language doesn’t light up your brains, it’s just a confusing reminder that you aren’t in the clubhouse.

Maybe you’re even a little annoyed with me.

Everyone likes exclusivity but no one likes to be excluded.

And what does it even mean?

It means that I committed the sin of punk.

The sin many businesses commit when they assume to deal with “ideal consumers who get brain sparks from buzzwords” rather than real people who don’t give two craps about brand language.

If you haven’t already made the journey to understand the terminology or tribal symbols, they mean less than nothing to you.

Make Some Noise

My first recording project as a solo artist was called “The Ondt and the Gracehoper”.

An almost impossible name for any living soul to spell, remember or understand.

A name that would scare away many listeners and confuse even more — but make the right people talk and a few think differently.

Today I’m less optimistic about human curiosity and would probably have chosen an easier name.

Though the music was almost equally pretentious — so maybe not.

To be perfectly honest, I wrote very simple pop tunes and dressed them in noise and heavy lyrics to seem more complex.

It worked to some extent:

Back in 2007 people had iBooks, MySpace, and music videos on national TV.

From name to sound, that project was pretty damn heavy on punk sins — deliberately to turn away satisficers and attract a more selective audience.

If you’re marketing a hard-to-sell brand — in this case the sound of a big ego with limited talent — you may rely on tribal signals to the select few and hope they spread the word.

In my case, it was mostly by adding noise.

Philosopher and cultural commentator Torben Sangild explains in his book “The Aesthetics of Noise” how noise can be anything, depending on context.

The soothing sound of the ocean can become the sweeping noise of a shortwave radio when taken out of context.

Noise can be a way to reveal by concealing. A distortion pedal physically limits the original sound of the instrument to reveal something new.

Noise is the paradox that is both music and not music.

Both an invitation and a rejection.

Both the journey and the war.

Lou Reed did it better.

As a copywriter I still try to make the most noise with what I got.

Though I tend to avoid heavy tribal signals.

The best planned strategy can become noise in the wrong environment.

But if anything can be noise — noise can be anything!

That’s when you need to think like an outsider.

Chapter 4: Truth or Coldplay

Monkee See, Monkee Do

I find Coldplay wildly fascinating.

Because they’re The Monkees of now — if the bald apes had stuck around for more than a few years.

In the late 90s, Radiohead had perfected the acoustic stadium rock ballad — and abandoned the recipe in 2000 with electronic genre breaker “Kid A”.

This left a hole in the market with plenty of satisficing listeners who liked the more accessible sound of old Radiohead.

That’s how we got Coldplay.

Catchy tune — but was it really “the new Radiohead”?

With acoustic hits like Street Spirit, Radiohead had left a proven template for melancholy indie-pop that was ripe for commercial optimisation.

Coldplay took it, took over, and eventually went from “new Radiohead” to “new U2” to whatever monstrosity they are now.

They found a sweet spot in the musical market that made them incredibly popular.

They didn’t change the world or revolutionize anything but they sold an awful lot of stuff.

The Coldplay model can seem pretty smart.

Use fewer creative resources and take fewer risks by adopting a proven template that isn’t currently dominated by competition.

But you’ll have no latticework to build from.

Coldplay became incredibly popular and sold lots of stuff.

Thom Yorke & Co succeed with a much harder-to-sell product to a huge audience — because they were credibly popular.

Radiohead still makes increasingly weird music, yet creates new markets for it.

Because they build from a true creative vision and the cultural tension it generates naturally.

They don’t need to write a brand narrative or put “authenticity” or “purpose” into words.

They just do it.

Because purpose is where you earn it.

If you have none, you can fake it for a while — but you’ll end up a perverted parody of yourself, chasing last year’s trends.

It takes a lot of bullsh*t to paint a picture big enough to cover up yet another self-righteous superstar with a secret Swiss account and virtually no substance.

That’s why Chris Martin talks an awful lot about saving the world.

Because his music does nothing to change it.

The sound of overprivileged 40-somethings chasing trends into oblivion.

Good creative work is not about selling illusion by repeating trends and predicting markets based on last year’s data.

It’s about giving humans new ways of thinking.

It’s about allowing others to imagine in a way that will not only sell products but make people enjoy them more — and for longer.

Why Billie is Brilliant

My new idol-ish

Wrong Billie!

Of any current pop artist, I think Billie Eilish has the strongest brand.

Everything about her tells the same concurrent story.

Sometimes with a boldness that Nike’s copywriters can only envy.

It’s the sound of Billie and Finneas, two siblings, singer and producer, sending beats and vocals back and forth from one end of their parents’ house to the other.

Two home-schooled kids in a loving creative environment (both parents are actors and musicians) who tell the story of their lives.

Listen to the breathy vocals and the intricate details in the bass that you only get with headphones. That’s the absolute sound of childhood bedrooms and unspoiled creativity.

Billie Eilish held on to baggy clothes and neon colors longer than the record label would have wanted her to.

It was an admirable fight for adolescence — even if it had made more short-term business sense to be unnecessarily sexy.

She took her own time. And then grew up and grew into something new — a full-blown Marilyn Monroe — still brimming with truth and all the cultural tension it creates to be good before hot.

Wholesome family values can look like anything.

Pop is King but the King is Dead

I’m old enough to have been slightly brainwashed by the 3-minute rule.

The rule dictates:

Verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus.

And if you get above 3 minutes, you should cut something.

The short duration of pop songs was born from technical limitations: What could fit and sound good on a 7-inch single.

Radio stations built their systems around vinyl singles and when the rule was no longer a technical necessity, most people had forgotten why it was even there in the first place.

Thus they assumed it was cut in stone.

The radio stations had no reason to change their systems because they could force more content into a smaller window.

Until radio died.

Maybe radio just killed itself?

Flow media tried to keep the model alive well even into the 21st century.

So we’ve kept repeating “you have to be Beatles-famous to make 5 minute pop songs.”

And hells to the no(!) if you should challenge verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus or its equally predictable variations.

F**k Your Best Practice

Billie Eilish has never heard of radio and has no respect for a best practice model that hasn’t been relevant in her lifetime

She tells the truest stories of Billie and Finneas through the channels where they resonate the most.

She annihilates systemic misconceptions of yesteryear and finds the sweet spot beyond conformity.

“Happier Than Ever” is a beautiful conclusion:

F**k your best practice.

This is creativity!

Don’t waste the time she doesn’t have!

As I’m writing this, “Happier Than Ever” has been out for exactly three months.

It’s got 88.342.297 views on YouTube and reaction videos are the hottest thing on the internet.

From screaming teenagers to weeping adults, this song hits with all the impact of unbridled truth and tension.

Billie Eilish hits the sweet spot where earned media, creative resources, and subversion of expectations make you see something in a different light.

It’s how great creative vision can give you a bigger perspective — whether it’s the Sex Pistols’ view of monarchy or the flexibility of the Nike brand ethos — and generate more value than it consumes.

That’s when creativity breaks the laws of thermodynamics and becomes magic.

On a planet running out of resources, such power might come in handy.

That’s why good advertisements are like good songs.

A truly great one can change the world.