What Misplaced Microtransactions Taught Me About Advertising

About the beginning of the end for BMW

Microtransactions have long ago made the leap from games and apps to real-life products and services. But they are a fickle construct, as BMW is about to realize.

The gaming industry offers excellent insights into microtransactions and the consumer reactions they cultivate.

Especially mobile games are a tried and tested battlefield for behavioral design and limitless upselling.

But it’s also where we learned the hard way that people will gladly throw money at subjective value but oppose disproportionally to practices they consider unfair.

Sometimes they rage quit altogether — and all together.

Which makes it that much weirder that even big brands seem to forget.

Like when Electronic Arts hoped anew that a full-priced Star Wars game could get away with locking Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader behind heavy-handed paywalls… And was struck back by the series-ending fiasco of Battlefront II.

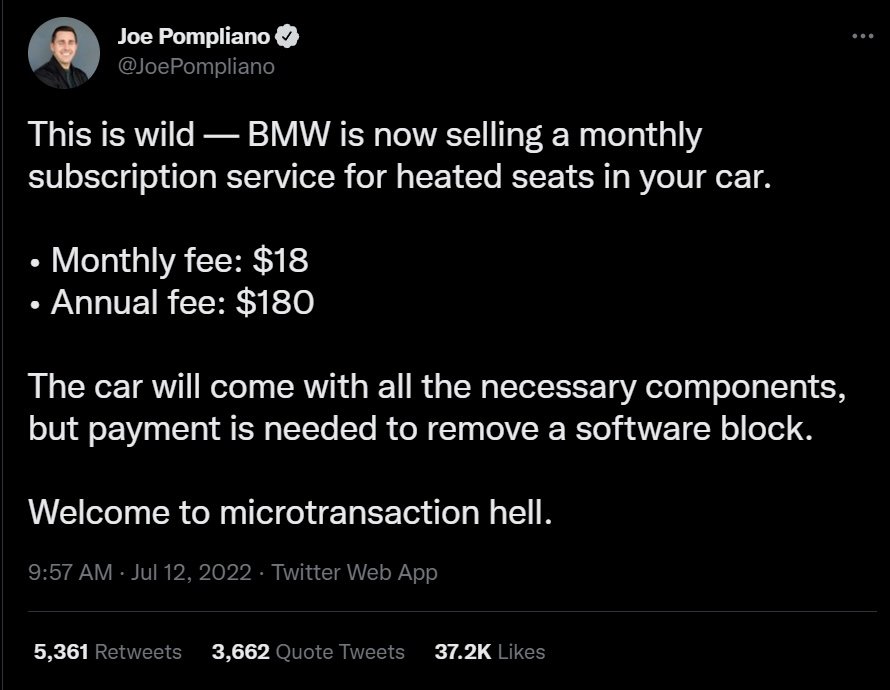

Or just last month, when BMW decided to turn off the heat in their car seats and instead offer “exclusive heating subscriptions” for $18 pr. month…

So… Yeah. That’s a thing now.

Microtransactions are a valuable tool for anyone selling anything.

They are a consequence of the digital age and they are here to stay.

But they are NOT a one-size-fits-all solution from free-to-play digital distractions that can be carbon copied onto already expensive automobiles.

In fact, I fear it will be the end of BMW as a luxury brand.

Here’s why.

Thanks for the Freemium

Microtransactions can be any kind of after-the-fact purchase that allows for an upgrade of a product or service.

They are the mechanical heart of the freemium economy.

You know them from apps like Spotify, Tinder, or Candy Crush Cashgrab where the entry is free but the road is hampered by annoying interruptions… that you can pay to get around.

Nudge, nudge, wink, wink.

Freemium services can get away with designing roadblocks because… Well, they’re free.

You get something without giving anything in return.

This triggers reciprocity and you are much more likely to accept paywalls and microtransactions as a way to “return the favor”.

Developers can slow the experience and make design decisions against the user because there are no feelings of ownership to offend.

There is no implied contract to break but plenty of loss aversion and reciprocity to nudge.

The Pain of Ownership

Video games that sell at a premium price can not use the same tools as their free-to-play relatives.

Simply because the paid entry comes with certain expectations of ownership.

If you paid €70 to dive into an interactive Star Wars fantasy, it might be upsetting to realize that you have to pay even more to unlock the central characters.

At least that was the lesson from 2017’s Battlefront II (a full-priced title) where Electronic Arts tried to use tactics from casual games and released the full fury of the internet… leading to the death of the franchise thus far.

If you’re unfamiliar with the inflation of game reviews: 68 is a low score. The user score, however, gives a pretty clear picture of the game’s reception.

There’s a fine line to walk for microtransactions in full-priced products.

Titles like Call of Duty make billions from season passes and in-game cosmetics without disturbing the game itself.

GTA 5 built an online experience separate from the main game where whales can get hooked unlimited — but the bigger community isn’t turned away because the core product is left untouched.

There are plenty of ways to offer microtransactions and succeed.

As long as they feel like upgrades — and not like paying ransom for something you already bought.

BMW in the Wrong Lane

Microtransactions can be hard to apply to luxury categories because there are no Veblen goods in the App Store.

Veblen goods are luxury products that contradict the economic law of demand because they are reliant on status and culturally subjective value.

In this upper echelon of commerce, there is no micro-transactional map to work from because digital products are comparatively cheap.

When BMW tries to break down the product experience into smaller entities, they do so because they want to be like Tesla and think like engineers.

They assume that their product and fundamental value proposition are as objectively clear to consumers as in the boardroom.

And they forget that they aren’t selling isolated parts but the psychological potent experience of complete luxury.

The trade-off when buying a discount product is that it’s cheap.

It might break, need repair, or otherwise cost you more resources down the road.

It’s the same thing with free apps. A lot of them are sh*t.

But when you buy a luxury item, the trade-off is the price itself, financial penance.

You go through the pain of paying more to make sure the experience is perfect.

The high price is the sacrifice that makes the item more meaningful, a totem in the personal ritual, a costly signal to the self.

Because sacrifice and ritual create bonus value — psychological alchymy.

It’s the precious aura that makes the consumer turn believer, the brand seem sacred, and the whole thing worth a lot more.

That’s the point of branding Veblen goods.

But famously, there is no faster road to failure than good advertising for a bad product.

And when the high-end experience is deconstructed and broken down into microtransactions, the psychological bubble can burst.

Once the cracks start to show, the magic is lost.

And so is any faith in the brand that would make up for the premium price in the first place.

Why Tesla Drives Revenue & BMW Will Crash

Even so, it’s long been common for car manufacturers to offer additional content of all sorts.

Tesla has refined this and introduced microtransactions with great success.

Because they make everything feel like an upgrade.

BMW thinks like engineers who assume the engine is the point while being warm is just a bonus.

And make consumers think that their costly luxury experience is suddenly less complete than a moderatly priced Volkswagen.

Because it’s not offering an upgrade — but blackmailing them with a downgrade.

And by doing so, fundamentally misunderstanding loss aversion.

If you know a little bit about loss aversion, you might ask if BMW isn’t just using behavioral psychology to increase revenue.

The feeling of loss is a much stronger motivation for buying something than the chance of gaining it. So why can’t it work?

Because loss is a strong trigger for action — not just buying.

At worst, unfair loss can make consumers boycott a product or brand entirely.

Like Battlefront II.

When free-to-play mobile games make loss aversion work, it’s because they build a framework of reciprocity, hot state decisions, and value anchoring — purchase 10 jewels now to continue before the time runs out! — without interfering with sensitive notions of ownership, fairness, or costly ritual.

And because brands like Zynga and King Games don’t exactly rely on solid reputations.

The same formula applied to Veblen goods can be devastating.

Is “broken aura” covered by your insurance?

But surely $18 per month won’t feel like a significant loss to someone who can afford a BMW?

Maybe not. But the loss of aura will.

The consequence could be the end of BMW as a luxury brand.

Unless they rethink their model or the rest of the category follows suit, this will be a nosedive in perceived position.

It’ll take time to see the results — but in a few years, we might find BMW in the same category as Toyota.

A well-engineered car, for sure… but hardly a status symbol.

How Advertising Can Help

I sometimes say that advertising is about designing beautiful journeys to ugly truths.

Because the object and the road to it are indistinguishable in the mind of the consumer.

The product and the experience surrounding it are one and the same.

But I’m wrong when only mentioning the journey to the product.

Because the journey afterward, with the product, is the difference between making a sale and gaining a customer.

It’s a driving force when building and maintaining brands.

“There is no sensible distinction to be made in a restaurant between the value created by the man who cooks the food and the value created by the man who sweeps the floor.”

Engineers and classical economists tend to suffer from physics envy and assume everything can be stripped to its basic elements and then reassembled with pure reason.

They see a logical reconstruction of value, while consumers see a psycho-logical loss.

It’s how BMW has taken the alchemy out of luxury and turned it into disenchanted disappointment.

Lose your faith in the brand even faster.

BMW stands by its USP of being all about engineering — only now it’s engineering a Frankenstein face for transparent greed that is being met by pitchforks and torches.

The result is short-term revenue at the expense of significant brand value.

Meanwhile, Tesla understands consumer psychology and how to make microtransactions work long-term:

By thinking about the complete user experience and not an objective product with isolated add-ons.

BMW: Good for bargain hunters. But does the math include loss of status?

Advertising knows when to sell holistic experiences, not disconnected features — though it can be hard to make clients listen (especially if you say “holistic”…)

And I realize that engineers are notoriously suspicious of consultants, creatives, and anyone outside the tribe.

Criticizing them here will hardly change any minds.

But at least outsiders offer insights.

We give perspective.

By writing this, I hope that I have too.

And I don’t even have a driver’s license.