What Clichés Taught Me About Advertising

About dead words, re-animated payoffs & how to use them

A cliché is an overused expression or trope.

The word itself comes from French, given to us by 19th-century printers who produced pre-made typesettings for oft-used phrases — simply to avoid arranging the letters individually every time a writer used an idiom.

These typesettings made a distinctive sound — cli-ché — and gave name to the onomatopoeic expression.

Nowadays the cliché has a negative ring to it — though more in meaning than actual sound.

A predictable trope or popular idiom can look like a letdown or just plain tacky in the wrong light.

So why do we use them all the time?

Well…

1: They are easy.

Instead of figuring out the exact words to perfectly describe something, you can just use a ready-made expression that gets close enough.

It’s a perfectly normal mental shortcut and a popular crutch for undisciplined and/or lazy writers.

2: Clichés aren’t all bad.

In fact, they can be downright hypnotic.

Let me tell you why.

Top 3 Clichés

Structural Clichés

Structural clichés are overused tropes, often specific to genre or media.

These are easy because they’ve been used in storytelling since humankind was a toddler.

And they are bad because they reveal themselves as tropes to the critical reader who’ll recognize the structure, guess the ending, and stop reading.

In Game of Thrones, when Ed Stark dies (spoiler), the oldest son, Rob Stark, is expected to avenge him.

George R.R. Martin uses the well-known fantasy trope to build expectation, only to destroy it when Rob Stark is murdered by his smoke-demon-nephew (again, spoilers for an old TV show, sorry).

An inexperienced storyteller might fall for the structural cliché because it feels right. But Martin knows that “feels right” is far from “big emotion”.

In advertising, structural clichés can make the reader / viewer stop paying attention almost immediately because the cliché screams: “This is an advertisement!”

On the other hand, using done-to-death tropes from different markets or categories can sometimes subvert expectations and capture the viewer.

Like this Postmates commercial that made me stop on my way to the kitchen, walk back to the TV, and check if I was having a stroke:

Idiomatic Clichés

An idiomatic cliché is simply an overused expression.

In his essay “Politics and the English Language”, George Orwell draws a line between “dead” and “dying” metaphors, where the dead ones are idiomatic clichés:

Once fresh phrases that have since entered the language as proverbial short-hand.

Such clichés are all over the place.

In both senses of the expression:

You see them a lot and they don’t have much focus.

But what they lack in evocative imagery, they make up for in well-knownness.

Where an original metaphor will make you stop and take notice, an idiomatic cliché can be a copywriter’s tool to paint a picture without breaking the reader’s flow.

As long as the idiom doesn’t contradict another metaphor (“the octopus of big data has sung its swan song”) these can be perfectly fine ways to build rhetorical bridges.

“A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically ‘dead’ has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness.”

Trending Clichés

Where Orwell accepts the dead metaphor as proverbial evolution, he is much more critical of the dying metaphor.

You hear it in industry speak, misplaced buzzwords, and copycat copywriting.

The dying metaphor is a cliché of its time, a possibly potent expression that’s been watered down by over- and misuse until it’s a kind of linguistic homeopathy:

A faint drop of something no longer significant.

An example from both advertising and tech is to “disrupt the paradigm” — often coming from people who don’t seem to know the meaning of either word.

(And just so you are not one of them: A “paradigm” is a model, system, or best practice in an industry, and “disruption” is to find the flaws in it. Eg.: What Netflix did to the movie rental industry.)

Those are the clichés.

There are more kinds, I’m sure. Like visual clichés.

But I went by the rule of three which is, of course, itself a kind of cliché.

When To Avoid Clichés Like the Plague

Structural clichés are the worst.

They can turn away a critical audience and activate mental ad-block because the tropes are so mind-numbingly obvious.

Where Netflix has found that their viewers prefer 80% cliché and 20% original, the same is not true for advertising.

If I sit down to watch an action movie, I probably want it to be mostly like an action movie. 80% recognizable and 20% surprising sounds about right.

But the second I recognize the structural clichés of a commercial, I start thinking about something else… Like where the skip button is.

Advertising can no longer look like advertising.

Idiomatic clichés are bad when they reveal themselves as lazy shortcuts, either unaligned or contradictory to the overall mental image.

Similar to how I used “avoid like the plague” above.

Without something thematic or linguistic to motivate it, it’s out-of-place laziness.

Hopefully, you dear reader, will accept clichéd headlines in an essay about clichés as thematically motivated.

Trending clichés lose meaning quickly because they tend to borrow authority or legitimacy from one context that doesn’t translate to another.

The flashy nonsense that can make the CMO super hyped will rarely have the same effect on consumers.

I am, for example, pretty sure my mom won’t care if I ever disrupt the paradigm.

“The inflated style falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outlines and covering up all the details.”

A careless cliché can give the wrong point of view, lead to the wrong train of thought, and arrive at the wrong conclusion.

Like a corporate manifesto using the car metaphor about “being in the driver’s seat” — great for the CEO with their hand on the wheel but a lot less so for the guy on the floor, now reduced to a bolt in the machinery.

Advertising is about giving the most beautiful perspectives on sometimes ugly truths — but a misplaced metaphor can do the exact opposite.

Every Cliché Has A Silver Lining

Don’t worry, clichés have their upside.

If everything you write is completely new and unheard of, it’s avant-garde poetry and not copywriting.

Recognizable elements are little islands on the journey for the reader to rest.

Clichés can be such islands.

And even better, they can add bonus meaning when used deliberately.

“To search under every rock” may be cliché in a detective story but in an ad about finding the perfect engagement ring, it might be kinda cute…

A well-used cliché can point the reading mind in a certain direction, build expectation, and then subvert it.

Both hypnotists and pickpockets know the persuasive power of the “interrupted handshake” — a trick where the brain enters an automated System 1-pattern (the handshake) and is suddenly interrupted — which leaves the person at the end of the hand in a suggestive state.

As explained in this video:

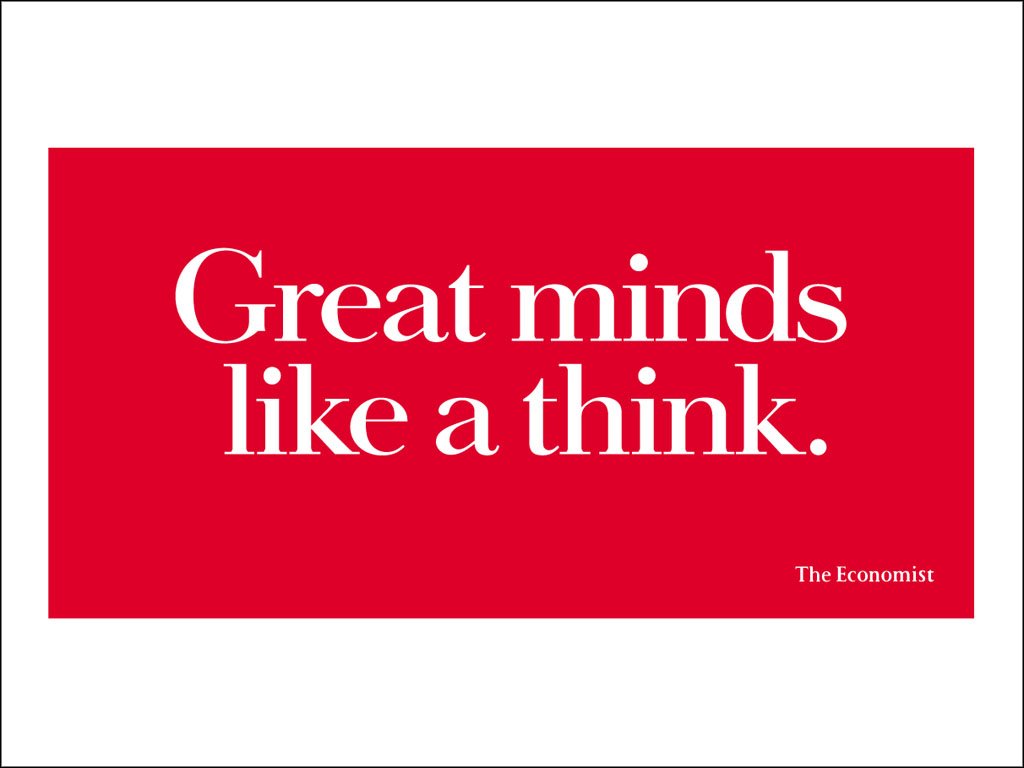

By using a well-known phrase and tweaking it to something unexpected, copywriters can make their own linguistic version of the interrupted handshake.

It’s how we can take dead words and reanimate them!

Because payoffs and one-liners that modify idiomatic clichés aren’t just trying to be clever or funny. They are sneakily persuasive.

Like this philosophical puzzle from IBM:

I don’t mean to imply that Descartes’ classic “cogito, ergo sum” is a cliché.

But it is certainly one of the most famous and overused quotes in all of philosophy.

That’s why it works so well.

The ad sends out a tribal call (during an era where computers were still new and for the few) that if you understand this, you are smart like us.

It appears exclusive in its reference without actually excluding anyone in the audience.

The deceptive simplicity of changing the letter A to B for a massive difference in meaning is equally impactful.

So much so that you may not even notice the suggestive effect of the interrupted handshake.

Everything can be a cliché if done enough. Especially when done poorly.

But when bridging old truths and new insights, clichés can be quite valuable too.

As long as you use them deliberately and carefully.

Why do less?

If you’re smart, you can even hire a freelance writer to sort them out for you*.

*I finished last week’s essay on a similar note. What a cliché!